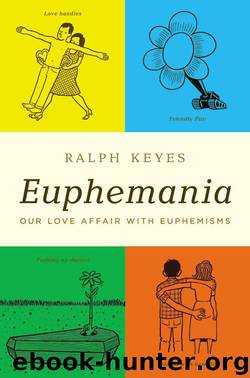

Euphemania: Our Love Affair with Euphemisms by Keyes Ralph

Author:Keyes, Ralph [Keyes, Ralph]

Language: eng

Format: mobi, epub

Tags: LAN000000

Publisher: Little, Brown and Company

Published: 2010-12-13T16:00:00+00:00

Never Say “Die”

When it comes to death, the euphemistic fog becomes nearly impenetrable. The dead are no longer with us. They left the building. Kicked the bucket. Bought the farm. They’ve gone home, or south, or west, or to the last roundup. They’ve laid down their burden. They’re pushing up daisies. Noting that the equivalent French expression manger les pissenlits par la racin literally means “eating dandelions by the root,” Hugh Rawson comments in his Dictionary of Euphemisms and Other Doublespeak, “It would be the French, of course, who would think of death in edible terms.”

It wasn’t always so. When death was more routine, so were the words we used to discuss it. Imagine a marriage ceremony that included “Till a fatal event do us part.” Or a prayer that went, “If I should expire before I wake.”

In the unsentimental Middle Ages, death was discussed freely, openly, candidly. Confronting death directly in word and spirit seemed to help our medieval ancestors cope with its prevalence. Works of art—paintings, statues, stained glass windows—brimmed with images of the dead and dying. Dancing skeletons were a common motif in the folk art of southern Europe (and still are in Mexico and other countries south of the U.S. border). Some early clocks were shaped like skulls to remind their owners that time was slipping away; death was on its way. Icons on tombstones didn’t gloss over what lay beneath them; they glorified it. A British church luminary named John Wakeman, who died in 1549, was buried beneath a monument adorned with a mouse, snakes, and snails feasting on his corpse. Well into the eighteenth century, skulls were the most common icon on New England gravestones.

This willingness to face death squarely extended to language. One 1615 book for housewives discussed how to deal with “Child dead in the womb” and offered counsel for a woman who “by mischance have her child dead within her.” A comparison of the 1662 Church of England funeral liturgy with its revision in the year 2000 found revealing differences. In the 1662 version, reference was freely made to “the Grave,” “the Body,” and “the Corpse.” Three-hundred and thirty-eight years later, “the corpse” became the deceased. Prescribed proceedings three centuries ago included this biblical passage: “And though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God.” Its modern counterpart deleted those words. Typical of the newer liturgy was the passage “Like a flower we blossom and then wither: like a shadow we flee and never stay.” Guy Cook and Tony Walker, who compared the two versions, dryly noted “an absence of reference to the physical facts of death” in the contemporary Anglican funeral service, which they attributed to “an unwillingness to confront the physical nature of death.” In America too, as Gary Laderman notes in The Sacred Remains: American Attitudes Toward Death, 1779–1883, modern Protestant theology treats the physical remains of the dead as “persona non grata, so to speak.” Avoiding direct contact with dead

Download

Euphemania: Our Love Affair with Euphemisms by Keyes Ralph.epub

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

A Dictionary of Sociology by Unknown(3073)

The Art of Dramatic Writing: Its Basis in the Creative Interpretation of Human Motives by Egri Lajos(3058)

The Dictionary of Body Language by Joe Navarro(2992)

0041152001443424520 .pdf by Unknown(2843)

How The Mind Works by Steven Pinker(2813)

Day by Elie Wiesel(2779)

Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Thesaurus, Second Edition by Merriam-Webster Inc(2752)

The Meaning of the Library by unknow(2564)

The Official Guide to the TOEFL Test by ETS(2325)

A History of Warfare by John Keegan(2238)

The Emotion Thesaurus: A Writer's Guide to Character Expression by Puglisi Becca & Ackerman Angela(2134)

Emotion Amplifiers by Angela Ackerman & Becca Puglisi(2030)

MASTER LISTS FOR WRITERS: Thesauruses, Plots, Character Traits, Names, and More by Bryn Donovan(1939)

Merriam-Webster's Pocket Dictionary by Merriam-Webster(1931)

The Cambridge Guide to English Usage by PAM PETERS(1909)

Star Wars The Rise of Skywalker The Visual Dictionary by Pablo Hidalgo(1887)

More Than Words (Sweet Lady Kisses) by Helen West(1853)

Lucky Jim by Kingsley Amis(1744)

American Accent Training by Ann Cook(1655)